Written by: Tiara Jade Chutkhan

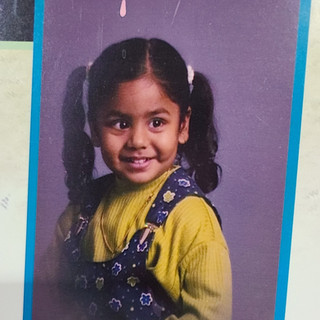

Since embarking on my personal journey of reclaiming and embracing my Indo-Caribbean heritage, I often find myself revisiting and unpacking moments of my childhood where my cultural identity was either questioned, dismissed, or a source of discomfort for me.

These moments often took place at school during interactions with my classmates and friends. Being young and tongue tied, I didn’t have the right vocabulary to explain my Indo-Caribbean heritage, let alone how I, as a Caribbean person, looked East Indian to most people. These moments made me uncomfortable and I dreaded any conversation where the topic of culture came up. The countries my parents were from, Trinidad and Guyana, weren’t places my classmates had heard of. They weren’t as easily recognizable as Caribbean islands like Jamaica, or South American countries like Brazil.

By the time I was in third grade, everyone became more conscious of the world around them. We would ask each other about what jobs our parents had, if we lived in houses or apartments, and of course, where we were from. “I’m half Trinidadian and half Guyanese,” I remember telling my friends proudly. As a child, my parents never explained Caribbean identity using terms like “Indo-Caribbean” and “Afro-Caribbean.” I was taught that Caribbean people came in many different shades, but we were all Caribbean, one people. I never questioned this explanation, but that didn’t stop others from questioning me.

“Where’s Trinidad?” “What’s Guyana?” “Why do you look Indian?”

My pride quickly disappeared. “I’m not Indian,” I replied. “You look like it,” they’d say. Did I look Indian? As far as my eight-year-old mind had processed, I looked Trinidadian and Guyanese. I looked like my mom, my aunts and my grandmas. I looked Caribbean. I had no answer for them. I couldn’t explain why I didn’t look like my friend, of Afro-Jamaican background, who fit the description of what others thought a Caribbean person looked like. I felt myself slide into my metaphorical shell, no longer wanting to take part in the conversation, or be asked anymore questions.

The following year our teacher asked us to bring in music from our culture so we could hear different sounds from around the world. Each week, my soca CD sat in the front pocket of my backpack, as I avoided volunteering. I ended up going last and the day my CD played, everyone was more occupied with games and fun to hear a single sound of the sweet music.

In middle school I made my first Indo-Caribbean friend. We were in 7th grade and from first glances I had a feeling she was either Guyanese or Trinidadian. Eventually we spoke, though I can't recall who first initiated the conversation, and I learned she was Guyanese. From the strength of our brown skin, thick dark hair, and the mutual understanding of each other, we became good friends and often hung out during lunch or in class. We would talk on MSN, freely using our Caribbean Creole, something I had never done with anyone before. She would ask me what my mom was making for dinner, to which I’d tell her curry chicken, stew chicken, and more without hesitation.

There was no need to explain ourselves, to answer awkward or ignorant questions. We didn’t use terms like Indo-Caribbean at the time, they weren’t ones we had heard before. But for the first time in my school years, and as I would later realize one of the only times, I felt understood and valid in my cultural identity.

In between my new found acceptance, there were still moments much like my elementary school experiences. That same year, while sitting in the school field with two of my other friends of East Asian background, a boy in my grade approached us and started talking. He made a comment that our little group was all Asian.

“I’m not Asian,” I said, correcting him.

“Yes you are,” he said in an aggressive tone.

We went back and forth multiple times.

“You’re Indian,” he said.

“No, I’m not,” I said, getting angry.

“Then what are you?” He asked.

At this point I was flustered, annoyed, and angry. I gave him my response and our entire interaction concluded with him telling me I looked Indian and walking away. In a matter of five minutes, I had been misidentified, invalidated, and completely ignored when I tried to correct him. Being told I looked Indian was usually the following word in most of my middle school encounters with the question of my background. People I’d known since elementary school, who knew what my background was, had seen my parents before, had heard my speech before, completely dismissed it. By high school, I tried my best to avoid these interactions altogether.

In my grade nine French class, on a day when we had a supply teacher and no work was being done, I found myself talking with the girl who sat behind me. Aside from saying hello to each other here and there and asking questions about what we didn’t understand, we hadn’t spoken much. “What’s your background?” She asked me, immediately making my throat go tight. Before I could answer, she continued her question. “You don’t look Brown Brown. You know, like Indian.” I cringed at her sentence. I was Brown. My skin was Brown. I told her yes, I was Brown, but from the Caribbean, my parents from Trinidad and Guyana. “Brown is Indian… so you’re basically Black,” she responded. We debated this back and forth for a few minutes before our conversation changed and much to my relief.

It wasn’t until I left the high school bubble that my experiences began to change. The people I met through jobs I worked, college, and other programs I took part in were usually able to tell that I was either Trinidadian or Guyanese, and just as I did as a child, I’d proudly tell them I was both. Meeting other Caribbean people was a comfort I had been longing for. Just as it had been with my middle school friend, I was comforted by being able to relate to others culturally and have them relate to me. There was no need to explain foods, language, music, and no need to feel ashamed, or hide those parts of me out of this fear I couldn’t be myself in its entirety.

My reason for reflecting back on these moments is to look at not only how far I’ve come in being confident in my cultural identity, but recognizing the discomfort these scenarios gave me, allowing myself to sit with them, and most importantly, heal from them. Growing up I often felt alone as I never heard any of my other classmates get asked the same questions or queries. Having now connected with other Indo-Caribbean folks, I realize so many of us have experienced similar situations. I take comfort in knowing that we can listen and share experiences with one another, as well as have these conversations.

Now, at 25, I no longer shy away from talking about being Indo-Caribbean (it’s actually all I do!) I step into my identity and share it with anyone willing to listen. Having learned about our history, our ancestors, our customs, and better understanding their origins has made me both confident and proud. I sit in this feeling often because it is still very new to me and one that I want to feel in it's entirety.

Comments